Being forced to live a life without grace, through our own choices or otherwise is not only a generic human experience, but one that takes specific forms according to the culture and society within which it occurs.xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

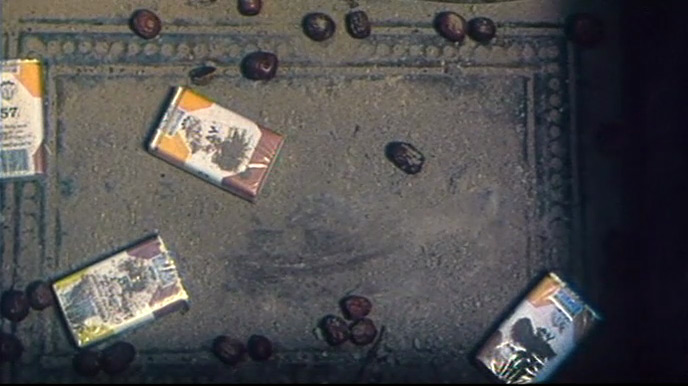

Dancing in the Dust, Asghar Farhadi's first film, is a powerful statement about the sacrifices we make in the name of society. It is about the whole history of loss, from one generation to the next—the accumulated private trauma—that people are forced to carry with them and upon which the stability and 'decency' of respectable social life depends. And while other of Farhadi's films show a more sustained focus on the Shari'a legal system and the way in which its structuring of the administration of justice intersects with the specificity of Iranian culture (its gendering, its pride, self-respect, need for individuals to maintain a dignified appearance in society), in this film, the story is much more intimate and personal. Where his other films are more ambiguous in their morality, here, the situation is quite clear: that by making decisions to preserve the appearance of respectability, the central character, Nazar, ends up having to sacrifice body and soul so that he ends up taking on the implements of a snake collector to hunt the desert for snakes for the rest of his natural born life, having given up all possibility of redemption. This is a film about the loss of our soul, the withdrawal of truth from life once decisions are made in order to preserve the appearance of decency. It is a story about abject life, being forced to live with the knowledge that we have made our own untruth in life by submitting to the mores of societal pressures within which the only glimmer of redemption that exists between those living this existence comes from the possibility of compassion that arises between same such people that arises out of the recognition of the absolute sacrifice each has made. It is about dancing in the dust, a title that so delicately describes the poetry of this film, at one and the same time expressing the alienation of a life of untruth without grace, as well as the small comfort that comes from the affirmation of that truth (which is all that remains).

It is in this sense that Farhadi's films have alot in common with those of Hong Sang-soo. What one understands in Farhadi's films is that these morality decisions are irrevocable: the culture that made them necessary prevents them from ever being revisited again so that all that remains is the resolute submission to the new reality they define. Once the snake catcher's wife leaves him after he is disgraced for a murder of passion, she can never again be seen with him. Likewise, having divorced his wife because of his mother's prostitution, he can only ever interact with her again through the polite distance afforded by civil society. These situations are presented in Farhadi's films in order to provide warning of the very real consequences of living life according to what we think of as its ordinary morality. And although Farhadi's films raise the possibility of making different decisions, ones that respect the real truth of their situation, his films don't provide guidance about how these choices might be made and how life might be led once they are made and what the cultural context looks like in that case: the problem is, rather, implied to be that of avoiding them in the first place and accepting the reality they produce for what it is, rather than correcting for them once they've been made.

In Hong Sang-soo's films, on the other hand, the issue has more to do with the structures and dictates of society that manifest at the subjective level and that lead one to freely make their own bad choices that are then subject to philosophical analysis in terms of the most appropriate way to live with them (or resist them). The director of Woman on the Beach can't come to terms with the fact that the girl he's interested in slept with a foreigner and so he struggles with images that don't conform to what he expects. The cultural valuation of purity becomes a psychological force that inhibits one from pursuing what they might otherwise prefer. In Right Now, Wrong Then, we come to see how a certain resignation to the failures of life provide the basis for a new form of confidence and resolve through which the serendipitous moment achieves its full potential to transform our lives. In these ways, the position of the social dictate moves from the purely exterior (societal) to the interior (psycho-subjective) that forms the basis for a new form of existential understanding. What is generally left as a cautionary moral tale in Farhadi's films, becomes the basis for exploring new forms of being within this same human abjection in Hong Sang-soo.

In this way, we may see the distinction between these two director's as one that is culturally produced and deeply influenced by their own particular philosophy and religion. In the case of Farhadi, it is the organization of society according to Islam and its Shari'a Law; in the case of Hong Sang-soo it is a culture influenced by Buddhist tradition shaped as it is by contemporary Western modernity, alienation, consumerism, and liberalism. In the former, the issue is how to deal with the totalizing logic of an homogeneous society and its laws and moral codes through which the particularities of individual emotional constellations become suppressed and inhibited; in the case of the latter, it is the absence of any such totalizing logic of society that opens up a space for the radical liberation of the individual into a new form of life. In this way, Farhadi's films might be viewed as an expression of his country's moral and religious conservatism within which no alternative appears as possible (only a poignant affirmation of its truth) while the films of Hong Sang-soo express the bottomless liberalism of its culture within which the possibility for a new way of living that transcends what are only social and psychological obstacles emerges.