Hong Sang-soo's 17th feature film explores the entangled relationship between one's disposition, the external environment, and serendipity.xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Fortune springs from the inside? I'm not sure...

The problem with writing about Hong Sang-soo's films it that of speaking about his film in a way that preserves its complexity, its intellectual and rational complexity, while also preserving or simultaneously expressing the emotional basis within which these complexities take on their proper meaning. This is also a more general problem of discussing the relationship between the objective content of language and, in the strict sense, its poetic content; or, the distinction between the signifier and the signified; or, that between the real and the virtual. But the problem is always particularly significant when it comes to Hong Sang-soo. Generally, with his films it is possible to reconstruct the meaning of the film by looking-out for moments in the film when a character will speak a particularly philosophical statement that clearly expresses something of more general significance beyond whatever the topic of the conversation within which the statement is uttered might hold. These are precisely the sorts of statements that are usually indicative of amateur, pretentious 'artsy' films, something a student might produce. Only in the case of Hong Sang-soo, they always fit perfectly into their specific moment and never (or, almost never) seem like naked philosophy being inscribed into the film, which is just a vehicle for their conveyance. As such, the problem is of accessing the background context, the completely implied and unspoken milieu within which such statements occurs.

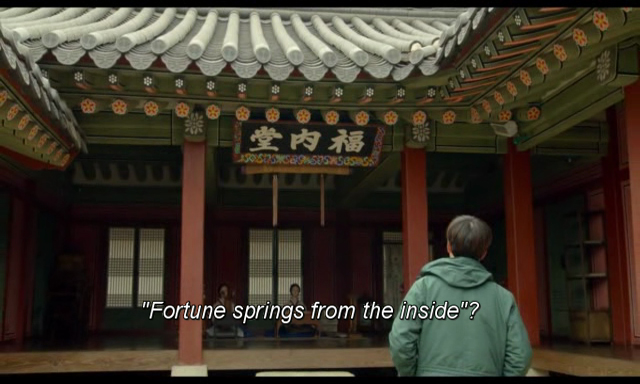

In the case ofRight Now, Wrong Then, one could take the moment when the director Ham Cheon-soo walks into the temple towards the beginning of the film and reads the inscription written above and quoted at the top of this article: 'Fortune springs from the inside'. To which he replies to himself: 'Fortune comes from within...I'm not sure...' This is precisely what the film is about: it is a kind of case study on this statement and an attempt to make it meaningful in its full and proper sense. It is a matter of the common fable that 'life is what we make of it', that 'we make our own luck', or that a problem we are facing is 'just in our head' and that our inability to move beyond a difficult or depressing moment is simply the result of 'looking at the bad side of things'. And its always the case that these suggestions have some value, its also true that in every such situation, there will always be external factors, things another person isn't aware of, things that are objectively significant to one but not to another that makes the act of simply 'seeing things differently' impossible or a matter of ignorance. And what further makes this slight shift of perspective difficult is the way in which our culture today expresses this positive approach and outlook on life, with its cult of identity creation and New Age creative living shuns anything that carries with it even the slightest hint of negativity or any attempt to introduce some bit of 'reality' into what seems to otherwise be on the verge of a kind of psychotic-delusional positivity. So, its particularly refreshing, then, that what we get in this film is an appreciation of chance and fortune that allows both sides of the argument to get some of what they want: for the realists, the film provides us with a pure objective perspective on the radical exteriority of luck and happenstance that has the potential to positively redirect our lives that exists irrespective of our efforts and actions; and, on the other hand, for the romantic-idealists we get an appreciation for a kind of system of ethics, attitudes, behavior, and comportment towards the world and others that allows chance the possibility of provoking a result in our lives. More simply put: while its true that our behavior matters, its is also the case that our behavior is not sufficient, that something else, some other element beyond one's own control must occur in order to 'produce' good fortune.

As with many of Hong Sang-soo's films, this one relies on repetition in its core structure to establish its point and proper significance. The film is divided into two parts, each of which follows the same sequence of events: a film director, Ham Cheon-soo, has arrived in a town for a screening of his film and to give a short talk and answer questions. He has arrived early in the town and has a day and night to wait before the screening the next day. To pass the time, he does sightseeing at a local temple and while there, he encounters an attractive painter, Min Hee-Kim, who he befriends and invites to coffee where the two have some conversations about art, their approach to life and other things. The two end-up going to her studio to see her paintings and, afterwards, the two have sushi. Then, when Min Hee-Kim realizes she has a prior obligation to meet some friends, the two go together to continue drinking at a party at which point the two repetitions of the film begin to more radically diverge. In the first half of the film, the interaction between the Ham Cheon-soo and Min Hee-Kim breaks-down with her pleading for him to leave her alone, she returns home to her mother, and he wakes the next to go to his screening where he is irritated by the moderator and walks out of the discussion and leaves the town hastily. In the second half of the film, the interaction between the two continues from the party as a love between them grows and they try to extend their night together romantically despite that Min Hee's mother wants her home. In the end, in this second half, he waits for her to sneak out of her mother's home, but ends up returning to his hostel after waiting in the cold, thereafter going the next day to a successful screening and talk of his film and, finally, a short encounter with Min Hee-Kim in the cinema through which their connection is reaffirmed.

Initial Conditions

What is it, then, about the second of series events that makes it so radically diverge from those of the first? To answer this it will be helpful if we can go through some of the initial differences, specifically, in the film:

- In the first half, the director is bored and arrived a day early, 'like an idiot'; in the second half, he gives a detailed explanation for why he arrived early that is based in a misunderstanding and having received a message too late to change his plans.

- In the first half, he eyes the young female assistant director from the window of his hostel and says to himself how attractive she is and that he 'has to be careful, its only a day'; in the second half, no such interaction occurs with the assistant.

- In the first half, upon arriving at the temple, the director can be seen distractedly checking his mobile phone before deciding to casually walk into the temple with his coffee; in the second half, the director is seen somewhat comically holding his coffee in his mouth while he struggles to awkwardly zip up his jacket to keep out the cold.

- In the first half, upon entering the temple, the director looks for a spot to sit in the sun to relax but is interrupted by a couple who come to take a photo and he leaves in irritation; in the second half, he is interrupted by a family and leaves out of respect to leave them the temple to experience on their own.

- In the first half, when he returns to the temple room to relax he sits in the shadow with his head on the pillar, as if such an uncomfortable position is the only one he can possibly find that he must just tolerate; in the second half, there is sun shining in the temple and he finds a place to sit in the sun and pulls his jumper over his head and clearly relaxes as music begins to play to reinforce the feeling of temporal discontinuity and the passage of time.

- In the first half, when Min Hee-Kim arrives, he immediately looks up to her and asks her if what she is drinking tastes good; in the second, he continues to relax in the sun until the noise of the top of her drink disturbs him and he looks over to see what is going on, at which point he then asks her if her drink is tasty, but in a much more casual, disinterested sort of way.

Already these six moments are enough to establish the qualitative difference between the first and second halves of the film that produce a distinct difference in the way in which the encounter between the director and painter unfolds that leads to their divergence. In the first half, the director is bored, he is passing the time somewhat irritably and would rather not have arrived early; his surroundings are something imposed on him that he wants to avoid getting too close to. Furthermore, his surroundings also reinforce his separation from them, making the difference something more than just individual choice: the sun is cold and not shining in the temple for him to relax in; there is an attractive assistant that makes him think of the necessity to withdraw immediately and frame his stay with cautious reserve; and he is bothered by a couple taking photos on their mobile phones who colonize the intimacy of his moment for themselves. In the second half, his attitude is supported by his surroundings: he is not unsettled by the attraction to his young assistant and his thinking remains unclouded; he is forced from the temple for a good reason, out of respect for a family to whom he willingly concedes the intimacy of the space; and he has sun to sit in and relax. There is a clearly a more natural, involved, in-the-moment presence to the second half that contrasts with the more removed, impeded involvement of the first half. Furthermore, there is a relationship, even a dependency, established between the external environment and the subjective disposition and behavior of the director in the two halves: in the first, the coldness and incompatibility of the environment that coincides with his more reserved disposition; in the second, the warmth and serendipitous alignment of the environment supports and coincides with his more open involvement.

First Condition: The Comfort of Failure and the Courage to Be

I used to hate that statue...but one day, strangely enough, that big statue started to make me feel more at peace, as if it was protecting me

In the first half of the film, the director is in a reserved position with respect to his early arrival in town: he wants to avoid any chance-encounters with his pretty young assistant that might lead to infidelity, he thinks himself an idiot for arriving early, he is checking his mobile phone, is bored and just wants to pass the time until the next day's screening. This is why how we find him at the temple meeting Min Hee-Kim. While it might be hard to guess at a deeper reason for this difference in perspective, the structure of Hong Sang-Soo's film and, again, some of its key statements throughout the film give us a clue. When Min Hee-Kim and the director are on the roof of her studio, looking out over the city and she is pointing her house on the hill out to him, she tells the director a story about a robber that once broke into their house but who left 'nothing but his tracks'; she then tells him about the Buddha statue on the corner by her house that always used to bother her with its imposing and forbidding presence that eventually began to give her a sense of peace. At this moment in the film we get the sense that the second half of the film, rather than standing on its own in a linear narrative, is, in fact, doubled by the image of the previously failed attempt in the first half of the film: at every moment, in fact, of the second half of the film, we are aware of the failures of the first half of the film that have the effect of opening-up a space of uncertainty and freedom of action that was not available in the first half. In the first half, free of any such image of failure, when the two are faced with a decision of whether to continue their interaction or not, one senses a feeling of anxiety about the potential for failure or uncertainty about where those choices might end-up or if they were the right choices (e.g., asking if the director will come to the party as well). In the second half, on the contrary, when the director asks Min Hee-Kim to join him for coffee, to see her work...there is a sense that it can't possibly end-up any worse than it already did: we ourselves have been lulled into a kind of peace with the unknown future between these two that comes, it seems, not from any single other place apart from the fact that the experience of failure in the first half of the film removes any anxiety, so that one can peacefully see how the second version of the encounter might turn out. In this sense, when Min Hee-Kim tells the director these stories about the Buddha statue outside her house and the robber who left nothing but his footprints, we begin to understand that these words refer not only to her own approach to these events and her life, but also to what emotional logic is is being produced in the structure of the film: it is the fact of failure and its invisible figure that towers over the second half that frees it from the fear of failure and that properly opens it up to the possibilities of the moment.

So, it is in this way that the director sits with his jumper covering his head from the world until he is interrupted by the popping sound of an opening container and only then decides to ask how the drink tastes; that he can immediately offer Min Hee-Kim an escape from the conversation that he himself is at peace to lose when he asks her if perhaps he is bothering her and that perhaps she would prefer to be alone; that he has the courage to probe her with personal and intimate questions about her life without fear of upsetting her since he is focused rather on getting answers to things he is curious about, rather than just making conversation to prolong the interaction he doesn't want to lose; that he can deconstruct her approach to painting and offer her such a critical but also constructive perspective based on his own deep understanding of artistic expression; that he can openly cry about his feelings for Min Hee-Kim; or to take his clothes off at the table amongst strangers simply because he felt hot. A history of failure has, in these moments, liberated the director and given him the courage to be simply who he wants to be, without thought or fear of the consequences of his actions.

This is also, however, what makes his behavior seem (particularly when he is crying at the sushi bar) completely naive: it is its ignorance of others judgments and of the judgments of the world (that renders our actions as failures) that restricts our perspective to ourselves and our own contribution to a situation, irrespective of whatever anyone else or anything else might introduce, that has the appearance of naivete and ignorance. In this sense, failure produces a perspective on the world that fragments along individualized lines, that compartmentalizes what is properly one's own and what is another's and is the beginning of what could be considered a truly multiple perspective that abandons the typical way of seeing life as somehow linked together at all times by objective abstractions and rationalizations. It is also in a certain sense the exaltation of innocence and naivete as something much more powerful and thoughtful than it is often considered: 'the power of words? What a joke...there's no such thing as important words!...they're just a hindrance.'

Second Condition: Serendipitous Support of the External Environment

An appreciation and experience of failure and the courage to be is certainly important to the events of the second half of the film, however, the film also shows us that it is not enough: the cooperation of the external environment is the second condition. Leading-up to the director's encounter with Min Hee-Kim in the temple, there are several elements of the environment that have this effect: the fact of being cold provokes the director to zip up his jacket; the shining sun in the temple that presents needed opportunity to relax; the loud sound of the opening bottle that disturbs the directors nap and provides the necessary impetus to speak with Min Hee-Kim without constructed pretext. Then there is the fact that, smoking outside the sushi bar, the director happens to find a ring on the ground that later provides the 'prop' necessary for making a mock proposal of marriage that lightens the mood at an important moment; the fact of the professor standing outside the cafe where they meet Min Hee-Kim's friends that evening that makes the cafe much more welcoming; the coldness of the late night that at all times makes them seek shelter together and focus on preserving the warmth of their intimacy; and, the final day, the falling snow. All of these aspects of the external environment support the director's disposition rather than oppose it. The cooperation of the external environment is what allows it to remain external. Conversely, when the environment fails to cooperate, when our movements fail to find support in it, we appear to ourselves as victims of that environment as it intrudes into our awareness. So, the director can arrive a day early and accept it so long as the objective facts of that arrival make sense to him as a series of understandable miscommunications and mis-timings. The environment appears as a neutral factor: it is simply what it is as external surrounding structure and not something warranting consideration, or that even becomes an object of consideration: it just suits the situation. When the director finds the ring on the street in front of the sushi bar in the second half, at the moment he finds it it doesn't appear to him of any significance for any other aspect of his life, just something unexpected he casually found on the street that he nonchalantly puts in his pocket; it is only later, in the midst of his conversation with Min Hee-Kim about his true feelings and his desire for marriage that it occurs to him, again as if by coincidence, that he does in fact have something in his pocket corresponding to the situation he then finds himself in.

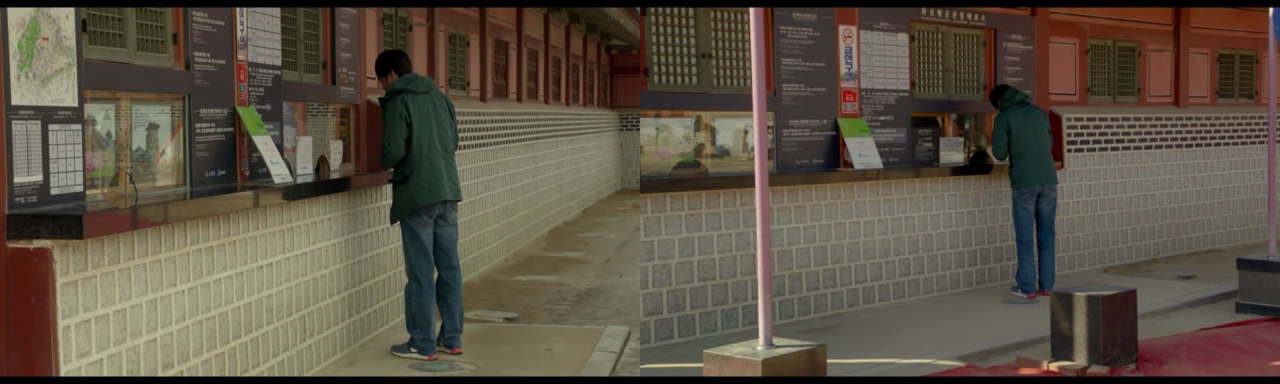

This aspect is perhaps the harder to discern (both in the film and in life itself). Perhaps this is also why the film provides assistance for this way of seeing: in the correspondingly external camera perspective and in choices for scene setup. For instance, in the first half, when the director purchases his ticket, the camera is situated with him, giving us the perspective of standing along-side him; in the second half, the camera is situated behind him, so we get the impression of being a voyeur, of something happening in an almost documentary-like way. Likewise, in the first half, when we first find the two drinking in the sushi bar, it is conspicuous that all of the bottles are located on his side of the table and the food (which she is eating, rather than focusing on drinking) is located on her side, giving the impression that the scene is the result of his own contrivance rather than simply given to them both that way; in the second half, these same bottles are closer to Min Hee-Kim and this, in turn, reflects her more active involvement in drinking (she pours the drinks and initiates a toast) which gives the scene an impression of being what it is as something shared between them and at the same time external to the both of them—a scene in which they find themselves.

But it is the scene in Min Hee-Kim's studio that is the perfect metaphor for this change in perspective. Seeing the painting in the first-half gives the two something to focus on between them and by being something to focus on between them it also becomes something that separates them, even though it may also give the superficial impression of being something they share; in the second half, the invisibility of the painting itself puts the focus of the conversation between them on what they actually share, which is that unspoken invisible bond developing between them, however problematic or contentious it is (they do, after all argue repeatedly at this point). This is reflected in what the director says about the painting: he tells Min Hee-Kim that she is seeking comfort in structures rather than confronting her real emotional involvement with painting and what it means in terms of her self-expression more generally. His point is that when we are open to the moment and are able to avoid seeking solace in immediately accessible representations (e.g., in the abstractions of language), and when the environment cooperates serendipitously and withdraws from acting as interference and as isolating, individuating force, it opens the way for the grace of good fortune and the emergence of a shared perspective that isn't something rational or explicitly articulated; rather, it is an unspoken,

implicated perspective, as two people navigating a stormy sea whose actions blend together in a harmony that coincides with a shared understanding of the environment and what must be done to survive the storm that they are in.

Third Condition: The Unconditional Return of the Other

When the director gives Min Hee-Kim the opportunity to abandon their conversation in the second half, he does so without expectation of her return; the fact that she doesn't abandon their conversation—entirely her own terms and outside of any organizing principle (trying to just get along, for instance)--is what makes her return so meaningful. When he gives her advice in the studio and she becomes angry, the director accepts the problem as real, as well as his own role in it, but also knows there's little use pressing the issue and so leaves to smoke, without expectation of her return; when she does decide, on her own and for her own reasons (perhaps of regret for being too harsh) to return to their interaction by showing him a nice place to smoke on the roof with a view, the situation between them is (re-)produced. This is also why, in the second half, rather than sharing with the others at the party the advice the director gave Min Hee-Kim privately in her studio, the bond between the two remains private and the dialogue between them becomes one of negotiating an approach to the social situation that preserves that privacy. And the conversation the two have the following day, when she shows up late for the screening in the falling snow, their intimacy is again protected by excuses that render it publicly ordinary ('she's someone I know from a long time', the director says) to preserve the integrity of their private involvement.

Concluding

In the final scenes of the film all of these elements come together to create something in which ones, as spectator also participates. Sitting there in the cinema preparing to watch the director's film, one hears what could be the soundtrack of a Hong Sang-soo film one themselves may have seen, perhaps HaHaHa or Like You Know It All. One remembers watching as two lovers searched for relief from the cold in a taxi ride to Kangwon Province (the title and location of Hong Sang-soo's second film). Our own experience and history as Hong Sang-soo spectators becomes activated. It is through these two moments that the film we are watching begins to withdraw and appear as something external to us as we begin to experience the shared reality that cinema gives us, a strange encounter with another kind of complex being with its own potentials and possibilities. One shares a history with film: the experiences they have had through cinema leave their own marks in one's life: the films one sees become implicated in a whole set of encounters and dark transformations that take-on a life of their own. Like meeting an old friend after many years, we come to the final scene after Min Hee-Kim finishes her final conversation with the director, he leaves, and she resolutely looks back into the screen, taking a deep breath before watching as the reality of her encounter becomes reflected in the images on the screen in front of her. And so it is, then, that as Min Hee-Kim exits the cinema into the surprise of a newly fallen blanket of snow that one, too, begins to see cinema and the world around us as something newly complex and charged with possibilities that may not have existed before the film began: cinema as a secular philosophical machine whose effects are transmitted in much the same way as good fortune graced the life of our director, Ham Cheon-Soo.

At the end of the day, words remain just words. The films, myself, my experiences, your lives—all of these things have nothing to do with words!