One of Eastwood's more tolerable films reveals the role of the Western mythology in deconstructing effective government as well as its emotional logic.xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

One must view any film directed by Clint Eastwood with suspicion. His films always find a way of expressing the conservative, small-government, individual-responsibility-Ideology that seems like it's a direct carry-over from his career in the Western. In the case of a film Executive Produced by the illegal foreclosure king of California and current Treasury Secretary of the United States Steve Mnuchin, one must be doubly vigilant. This is because, generally, Eastwood's films look with contempt on government workers, on those that attempt to uphold the public's interest, and on those who, ostensibly at least, act according to any kind of social morality, casting them usually as petty, cynical little men motivated by their own political aspirations, or as totally misguided in the critiques they raise that miss the solid gold quiet dignity of conservative motivations. Precisely, in fact, the way they are most commonly portrayed in the Western (and other ideologically conservative content. In this way, Eastwood's films can usually be seen as a Western morality transposed into some other contemporary situation. Sully is no different in this respect and there are two things about the way in which Eastwood does this here that are worth considering.

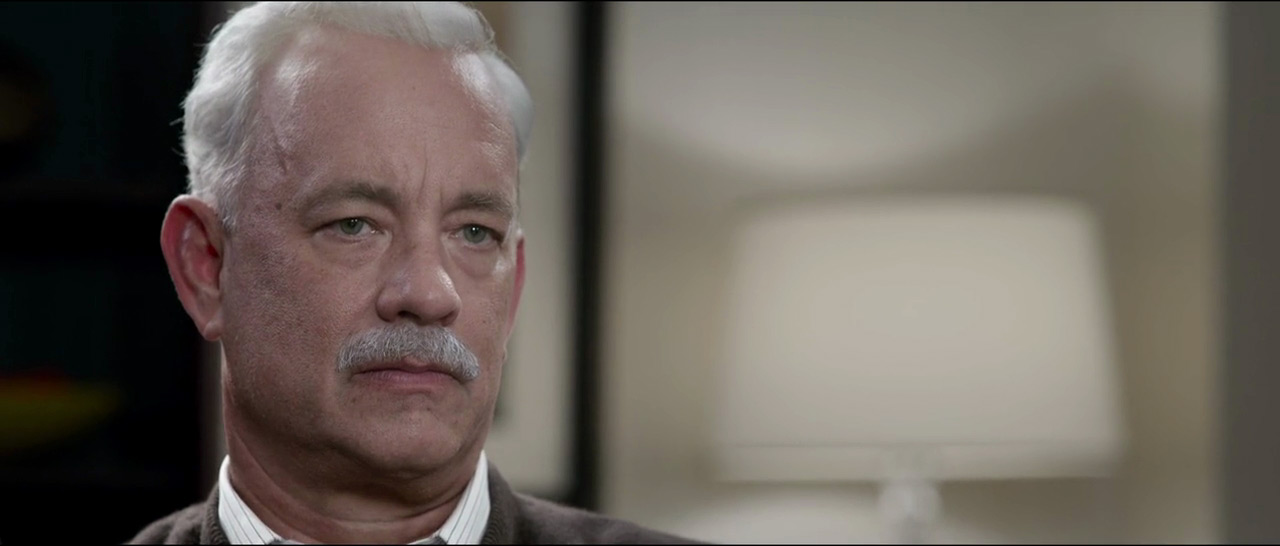

First, the approach Eastwood takes is that from the very first moment the NTSB begins its investigation it is taken as self-evident that what the captain did was heroic. It is, in fact, so self-evident that anyone who learns about it, who sees it on the news, can agree1. The problem with this is that it, primarily, is in the public interest to know precisely what happened. Upon learning that there were, in fact, other options available to the captain that may have produced a better outcome and avoided the risk to life and loss of the plane of a water landing, it would be incumbent upon anyone in the position of investigating the event scientifically to ask, in detail, what it is precisely about the situation that the captain faced that differed from the situation as it appears to an external observer that make the captain's decision justifiable and correct (or, on the other hand, erroneous). Secondarily, it goes without saying that such a scientifically motivated investigation and the precision it demands (corroborating multiple independent viewpoints) should have nothing to do with egos, with supporting one (political) narrative over another, and everything to do with the procedure of objectively assessing what happened. While Tom Hank's portrayal of his character certainly shows us a person taking the investigation in stride, someone who feels, rightfully, troubled with the thought that he could have made it back to the airport, Eastwood appears to exploit his star cast-member's performance to transform the captain's dignified tolerance into that of a victim of circumstances that are beyond his control (reflected in his clearly overly dramatized and too-persistent and obvious to miss puzzled sincerity). It is on the basis of this (elevated, martyristic) tolerance that the agency's investigation is cast as unnecessary and unwarranted, indeed an affront to common decency and purity of human spirit, rather than through any real rational discussion; it becomes the way in which what should be a purely objective issue (of learning the details of the crash) is transformed into a purely private, personal issue of respect and decency. This is the way in which the dynamic is framed from the very first moment, and it is the reason (in addition to many moments of interestingly stilted dialogue2) to look at this not solely as an aspect of artistic license but, rather, one of ideological pre-disposition.

Second, while Eastwood does refrain from completely slandering the NTSB (even they are forced to recognize the captain as a hero when the evidence finally substantiates its obviousness through the apparently indecent and unnecessary public hearing), what is interesting to note is Eastwood's seemingly limited perspective when it comes to the contemporary functioning of government. Stuck as he appears to be in the cinematic black and white of the Western, in the easy morality of bad government versus good individual, he seems to have missed the transformation that has taken place in the United States during the past 30 or so years3. At one time in the past, it may have made some (philosophical, perhaps) sense to look at the government as that which was inhibiting the free expression of humanity's individual potential, that communism and socialism were things to be fought, perversions of the human spirit that end in gulags, the Stasi, and the stultifying conformity of a place like North Korea. Today, however, when all major functions of the government have been taken over by large corporations and the wealthy who's only goal is to undermine them to the point where cannot properly function and fulfill their mandate or, on the other hand, turn them into simple enablers of industry, it seems a perspective that is barely tenable anymore. In the situation as it stands today, the real story that Eastwood is missing is not the tired and anachronistic story of bad government crushing the spirits of the individual with its base political motivations, it is the story of a set of government agencies who's sole purpose is today to do the bidding of large corporations. In this sense, if there is blame to be put onto the NTSB in Sully, it is certainly not for wanting to conduct an investigation, which is by law its right and mandate; it is certainly not for wanting to ensure that the public interest is upheld over the long term and that regulations meant to ensure the stability of airline industry are adhered to over and against what might be best for a single individual at one moment in time (i.e., of their public glorification); rather, it is that the NTSB of today probably has an agenda to produce findings about crashes (and the ubiquitous maintenance oversights and outsourcing and other issues of public interest concerning airline safety) that limit airlines' financial and legal liability. It is not the actions of the government agency that are really any longer the proper location of valid critique, but the way in which they function in a mode of corporate take-over that produces the agency's decisions.

It is in this way that Eastwood conflates the actual problem of the conservative corporate take-over and dismantling of government functions with the issue of big government's cynical-nefarious political motivations. And this wouldn't be a problem worth highlighting if it weren't so common a theme. The problem today isn't less government, its problem is effective, independent government that is democratically accountable. In this sense, what we see in this film4 is the way in which a mythology deriving from the Western and America's Frontier individualism allows people like Clint Eastwood to disingenuously5 undermine even the very concept of effective government (not to mention actually dismantling it) and the emotional logic according to which it is accomplished6.

Footnotes

Which makes it strange when Eastwood takes the opportunity to criticize the adoring fans of the captain, in this scene in the bar where the jabbering group of jackals just can't seem to shut-up and take the event seriously. So, on the one hand you have the adoration of the crowd that forms part of the legitimacy for the captain, that he is a hero who should unquestionable be accepted (since it is only the NTSB who refuses to acknowledge the universal fact), and, on the other hand, the crowd is that which never really understands the depth of emotion Big Men, men of consequence have to endure. ↩

These moments of stilted dialogue are a basic characteristic of Clint Eastwood's films. On the one hand, they seem to betray an ineptitude in directorial skill; on the other hand, they may also reveal an impossibility to translate an untenable ideology into natural inspirations for his actors, who are forced to perform roles that find no basis in their (or anyone's) actual humanity. ↩

Which, not coincidentally also corresponds with the time during which a conservative politics has dominated both major political parties in the U.S., particularly since his fellow Western actor Ronald Reagan held office ↩

And Eastwood's films more generally, for instance his recent film American Sniper is a good example of the way in which the mythology and nearly religious glorification of the military has enabled the United States to wage war continuously for the past 15+ years. ↩

Since it is too pervasive and predictable, too dissonant anymore to attribute* as a product of pure naivete. ↩

Which, perhaps coincidentally, mirrors the politics pervasive in the U.S. today: where, rather than substantive debates about issues, conflict is manufactured around emotionally charged issues like abortion or race AROUND WHICH THE SYMPHONY OF FUCKIN' libtard!!!! is played forever and ever more ↩